Thawing

My Yale published essay about becoming my own hero.

(Warning - this piece contains intimate themes and adult content)

“If you chew ice right now I will never forgive you,” said the teeth to the body. She dumps the cup into the sink and wanders down the hall. Along the way, there are spaces where picture frames ought to be. She tries to keep her left hand from knowing what the right one is doing, but the left one always figures it out.

“Hey! Is that a cigarette? Put that out!”

The girl sits down to read a book, but her eyes wander to the margins. There is a tiny drill sergeant knocking at her brain. It wears a black tuxedo and carries a baton. It tells her to quit her job. It tells her to move to New York. No matter what she does, it tells her she’s doing it wrong.

She wants the sergeant to shut the hell up. She uses whiskey like a little pillow over its mouth.

The girl tries to read, but her eyes won’t unstick. She sets the book aside and wonders how to fill the time until she dies. The days yawn before her like a daunting and undulating horizon, another sixty years at least. All at once, she thinks she is selfish. She is selfish for being so healthy and bored.

The girl makes a dentist appointment. She hangs up the phone. Her body is ripe for touch, and it looks around for someone to have sex with. New York is a big city, and maybe she will find someone right outside her door. Maybe men are falling from the sky, ones with blue eyes and French tongues, who look and feel exactly like her ex; who are just as smart and just as strong and just as absent.

She wants to consult her heart, but it is nowhere to be found. It always does this. It always wants to be the brain, think brain thoughts. At night, the heart looks itself in the mirror and tries hard to resemble sponge matter, closing its eyes and willing the pinks to gray.

The girl thinks to call her mother, but the mother won’t pick up. The girl thinks to call her father, but he’ll just ask about the weather. She sighs and looks around.

It’s ninety two degrees in her bedroom. She takes off all her clothes. She likes to be naked. She is always stopping to look herself in the mirror, feeling thrilled by her plump breasts, then feeling seized, suddenly, with sadness like waking up from a dream or watching a cloud slide into view.

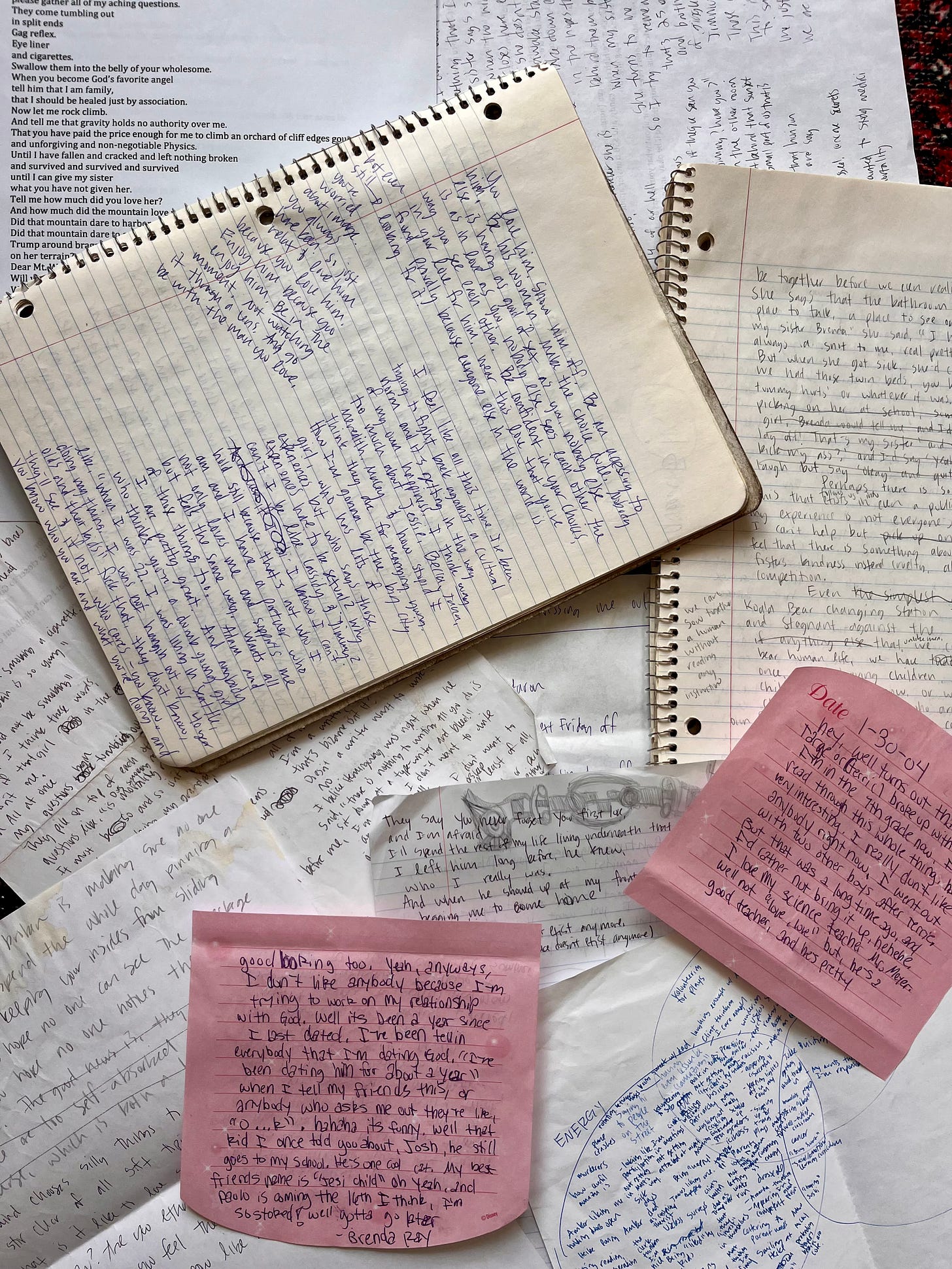

She opens her notebook and begins to write. Something lets loose inside her. She thinks if she just keeps writing like this every day, everything will be okay. But soon the sentences get away from her. And the heart slips loose from the cavern, stiffening and muting in deft rigor mortis. The girl wants the heart to come back. She loves the heart exactly as it is.

She sets the notebook down and puts her hand between her legs. There is an orchard down there with fruits hugging themselves into bundles and folds. She pulls until the orgasm spills out of her like silk, running down her legs and onto the bed like generations of sought after gold.

For a moment she is quiet, and the eyes are like two heavy dams holding water back. She wants to orgasm the way she did when she was younger, all that hope flowing forward into her lover’s palms.

Her body wants to be touched without owing anything in return. Her body wants to walk down the street without being whistled at.

The dam breaks, and the tears spill over her, down her breasts and onto her thighs. The sergeant is quiet.

She thinks to call the ex. If she calls him he will answer, but the ex is far away, hours by plane. It is morning here, which means an even earlier morning there, an even earlier year, in an earlier life, in an earlier world. She keeps having the same dream. In the dream, there is a big house, and she searches every room. He is always just one room away; he is just on the other side of that door.

She doesn’t know why he looks so much like an answer. He cannot bring bodies back from the dead. Unwind the cancer in her mother’s veins.

She wants to protect him from her sharp corners. She shuts her mouth tight. The girl remembers the wintered past, stumbling into parties, and the dark fire lighting up her mouth. She can’t remember what she said only his face when she said it. Every morning she would trace the contours of his back with sorrow unbuckling in her chest.

The girl shifts on her mattress. She decides not to call.

She has looked everywhere on planet earth for the answer. All the usual places to start: the bottoms of bottles, on tables in bars, penises, countless penises. And then she started looking harder: church, photographs, running away and holding still, looking and not looking too. Her vices are boring. How many different ways can she poison herself? How creative can she be, really, before it all winds down to the same muted tragedy, a warm cheek against the tiled floor?

She has looked every place on planet earth except one, and that is in her -in her body, her heart, her mind. And that’s the answer. That’s the fuckin answer isn’t it? She knows it, the way you know your mother’s voice calling your name. Except when you’re the answer, it is not the gift that keeps on giving, in fact, it doesn’t give at all. In fact, she has no clue what to do except sit in her silence, sifting through thoughts.

On the mattress, a moment or two passes when the girl feels it coming. A sadness so deep and unknowable, she cannot reach the bottom. Then it’s there, in the room, coming towards her. She squirms away but it’s too late now. She can see her mother in radiation, the paper skin gathered amongst the IVs. She sees her father, waving at her with a glazed pair of eyes. Of course, she sees her sister, dancing at the wedding. Her brother-in-law, a sharp diamond on the morgue table. If I am the answer, she thinks, then I need to bear it. So she stops. She waits. Her hands unclenched, un-reaching for a single bottle, a single drink, a single thing. The sadness rolls over her, and she lets it bend and fold her body until finally, at long last, it lets her go. Everything she has ever needed to know she knows in her body. She feels the tiniest pin prick of god then it’s over.

She gasps on the mattress. It let me go, she thinks, so that’s it then. So that’s pain. She starts to cry. The tears are different this time. The girl is in awe of the tides, in awe of the way the body can bear its choices. It will get easier, she tells herself. She doesn’t know that for sure, but she says it anyway.

After a moment or two, she catches her breath and decides to find her way back to the center. She has wafted so far from shore she can’t recognize her own handwriting. She thinks she ought to write more, remember earlier when the pressure let loose? What was that teeming inside her?

She wants to be her own mother, but she is running out of examples. She thinks she can remember every good thing anyone has ever taught her. She makes a list of all the things she wants to be.

Kind.

Forgiving.

Grounded.

Strong.

Warm.

Honest.

Brave.

Humble.

Patient.

The girl thinks hard about her choices. If she wants to be these things, then she must start by going outside. So she stands up. She does not know where she is going, but going is a good start. Maybe she will see the sun or make a friend or hear a child giggle in a department store. She puts on clothes.

When the girl is dressed, she sees herself in the mirror, and stops to look. The woman staring back is tall and unblinking. In her eyes is a fire so bright, no ocean on earth could put it out. For a moment the girl stands there, staring. The woman stares back with a gaze so steady, the little girl feels like she is strong all over again, like the strength is rushing to her organs. And together they just stand there, looking at each other, knowing what is unspoken, knowing that the woman is inside her, that she is the mother and the father she craves. She is the dream she believes in. After a moment or two, the woman finally says what the little girl already knows deep down in her heart but needs to be told again and again.

“Yes,” she says, “You are the answer.”